If you’re a ’90s kid like myself, there’s a good chance you’ve at least heard of Sailor Moon. If that was a little too “magical girl” trope-y for you, maybe Dragon Ball Z? Either way, there was a good chance you were tuning in to Toonami after school and part of the revival and eventual ’90s boom of anime in America.

Astro Boy was the first anime to be broadcast overseas, premiering in the ’60s, and considered the first animated series to utilize the aesthetic of what we know as anime today. However, it took about thirty years before anime really came into popularity in the US, with the first AnimeCon held in 1991. Of course, Sailor Moon and Dragon Ball Z rode in on that ’90s popularity wave, along with Digimon, Cardcaptors, the still-airing Pokémon, and others.

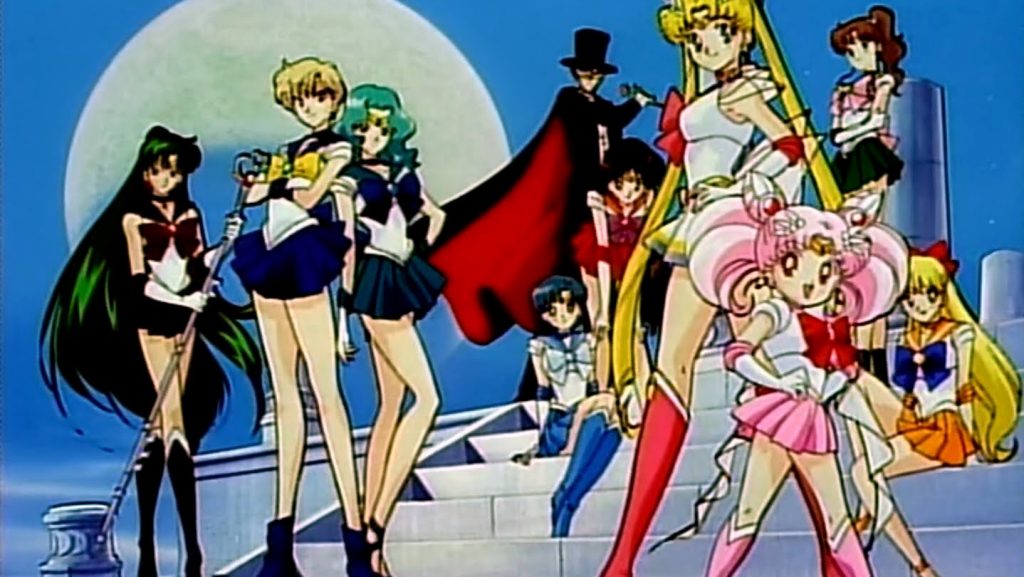

Prepubescent me, however, only had eyes for the Sailor Soldiers fighting evil by moonlight. Sailor Moon had it all: comedy, action, magic, romance, and young women. A lot of young women. Most of the heroes, and even the villains, in Sailor Moon are women. Yes, there’s Tuxedo Mask, but he mostly serves as our heroine’s love interest, and I think fans have to admit his rose-throwing is hilariously absurd. Of course, preteens thought it was romantic AF, but as the series progressed, Tuxedo Mask’s role became more peripheral as all the women of the series began to overshadow his capabilities.

Image: Toei Animation

I was an extreme fangirl and obsessed with Sailor Moon. I’d watch it every single day it aired in 1998 and, if for some reason I wasn’t home to watch it, I’d record it. To this day, I have tapes and tapes in storage labeled in my juvenile handwriting. It didn’t take long before my room was filled with Sailor Moon memorabilia such as posters, playing cards, stickers, jewelry boxes, and even a seven-foot banner to hang on one of my walls. Little did I know I was in for a rude awakening when my favorite anime obsession would suddenly stop airing—no more Sailor Moon. Of course, this was due to the company change in rights holders, from DiC Entertainment to Cloverway Inc., and the new company having to dub and edit more episodes. But I was young and without the internet and honestly thought my Sailor Moon viewing days were at an end.

Prepubescent me, however, only had eyes for the Sailor Soldiers fighting evil by moonlight.

But how could this be? Sailor Moon’s adventures were certainly not over. There were so many questions left unanswered, characters unexplored, villains still at large, and transformations unseen. Despite my disappointment, I wasn’t without determination, and it didn’t take long before I was dragging my mother around New York City, seeking out other means of viewing my beloved Moon Warrior and her celestial posse.

My mother and I found ourselves scouring all VHS stores in lower Manhattan, starting in Chinatown and moving north. I found my VHS mecca in Chelsea. Walls were lined with anime tapes, and my eyes moved from title to title: Gundam, Yu Yu Hakusho, Cyborg 009, Dragon Ball, Neon Genesis Evangelion . . . Suddenly my eyes grew big as they landed on the Sailor Moon box covers. Labeled Sailor Moon S, Sailor Moon SuperS, Sailor Stars, those names meant nothing to me yet. Where even to begin?

At about ten dollars a pop, my mom would only allow me two on my first visit. Fortunately, there were about four episodes on each tape, which meant there were eight moon magic–filled stories waiting for me. I started chronologically, beginning with Sailor Moon S—the Death Busters arc. Popping in the soon-to-be-obsolete VHS tape into its soon-to-be-obsolete player, my Sailor Moon universe was suddenly vast.

Sailor Moon was no longer Serena but Usagi. Darien now Mamoru. Rini now Chibusa—and thank Japan for that because I hated that English-dubbed name. All the Scouts’ names were different, and the Scouts weren’t even “Scouts” anymore; they were “Senshi” (translation: warriors). I loved that! These weren’t girl scouts; they were WARRIORS. They weren’t selling cookies; they were kicking ass and taking names. There was more violence, bigger stakes, darker themes, and new characters.

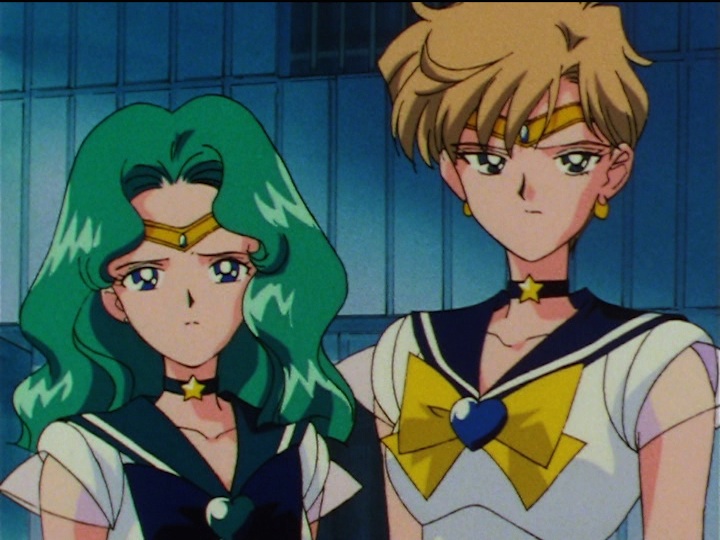

Enter Sailor Neptune and Sailor Uranus. Neptune, aka Michiru, a violinist with a lot of attitude and elegance. Uranus, aka Haruka, a video game lover with equal parts aggression and chivalry. Haruka is so chivalrous and charming, in fact, that two of the main characters become enamored with her after mistaking her for a male student.

Sailors Neptune and Uranus. (Image: Toei Animation)

It soon becomes apparent that Haruka and Michiru are romantically involved. Similarly to Xena: The Warrior Princess, there is a lot of sexual subtext, which includes intense glances, vague innuendos, and hand-holding. Their strong romantic feelings culminate in an emotionally intense scene between the two, which flashes back to an intimate tryst between the two, hands entangled and Michiru’s wet hair cascading over her casually unbuttoned shirt. The sexual tension is palpable, even to an eight-year-old of the ’90s.

Now, the show never bothers itself with the label of “lesbian,” so I didn’t either. All I recall is the loving relationship between two women. And, like many other fans, I became invested in their relationship, rooting for them as defenders of the universe and as a couple. Unfortunately, most American audiences never felt those emotional stakes due to the American censors drastically changing the nature of their relationship. Instead of lovers, Haruka and Michiru are portrayed as cousins in the English dubs, recontextualizing all of their scenes together and making some of them downright awkward.

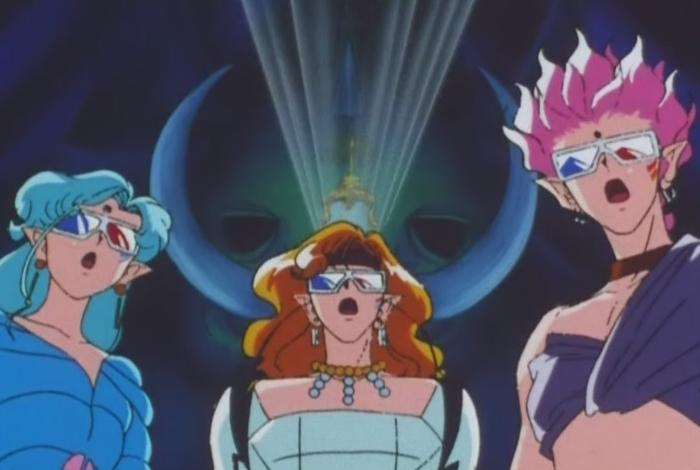

The next change relating to sexuality went entirely unnoticed in the English-dubbed version. The following season, Sailor Moon SuperS, introduces the Amazon Trio as the the first major antagonists of the arc. Consisting of three members—Hawk’s Eye, Tiger’s Eye, and Fish Eye—the Amazon Trio is tasked with looking for a magical Pegasus in the dream mirrors of mortals, a standard Sailor Moon plot. Choosing their victims based on their attractiveness, each member seduces their target before attacking them when they’re most vulnerable.

The Amazon Trio: Fish Eye, Tiger’s Eye, and Hawk’s Eye. (Image: Toei Animation)

It is established early on in the season that all three characters are male. When Hawk’s Eye and Tiger’s Eye are feeling a little indecisive about their victims, in walks Fish Eye, who is immediately smitten with an image, seizing it with blushed cheeks and gleeful excitement. After asking for permission to pursue the target, both Hawk’s Eye and Tiger’s Eye lean in to take a look. They both express shock and disgust at the photo as it’s revealed to be a man. “I thought he had been a little suspicious all this time,” exclaims Hawk’s Eye. After musing aloud about what kind of girls the target likes, both Tiger’s Eye and Hawk’s Eye declare they’re all “boys.”

Nearly all of Fish Eye’s victims are portrayed as heterosexual males, with a gay fashion designer named Yoshiki Usui being the only exception. Usually Fish Eye cross-dresses when seducing targets; however, he approaches Yoshiki as a handsome male, and the designer describes Fish Eye as a “miraculous person who surpasses gender.” While featured in some films, usually for comedic effect, this was a mostly unexplored concept for America’s mainstream media. Thusly, Fish Eye was simply changed to be female for American audiences. Overall, four characters were gender-swapped when the series was brought over to America, Fish Eye being the fourth.

Before making it to American screens, Sailor Moon was heavily edited and censored in numerous ways. The changes made to Sailor Neptune, Sailor Uranus, and Fish Eye were all part of the conformity to heteronormative narratives. Changing genders was extremely easy with a character like Fish Eye, as he was an effeminate character who donned women’s clothes and presented as female most of the time. With Neptune and Uranus, the change from being lovers to being cousins was a lot more awkward and something viewers certainly picked up on.

The changes made to Sailor Neptune, Sailor Uranus, and Fish Eye were all part of the conformity to heteronormative narratives.

The Sailor Stars season was an entirely different matter, however, with a storyline that couldn’t simply be censored away. In the end, the American broadcaster at the time simply chose not to air the season at all. The controversial reason for this is the introduction of the Sailor Starlights, three male pop idols who could magically transform into otherworldly female warriors. It’s later explained that the Sailor Starlights chose their alter egos in an effort to attract their lost princess through the power of song. Again, makes perfect sense for a Sailor Moon plotline.

While in the guise of idols, they meet and befriend the Sailor Scouts. One in particular, Sailor Star Fighter/Seiya, becomes very close with Sailor Moon/Usagi and ultimately ends up falling in love with her. As all fans know, Usagi is already fated to be with Mamoru, so we all know this is a doomed courtship. This doesn’t diminish Sailor Star Fighter’s feelings at all, their love expressed in both alter egos with little attention drawn to gender identity or transformations. It’s just simple love between two characters, genders not considered.

Censorship is a long-discussed and debated topic with ideas of appropriateness varying from country to country and changing over time. Of course, the original Japanese series had its own problematic plot points, such as the “Usagi Will Teach You! How to Lose Weight” episode, which has a lot of fat-shaming in it. But, narrowing the scope to just the handling of gender and sexuality, American fans were shortchanged.

Most American children of the ’90s never grew up with the smoldering passion of Uranus and Neptune . . . or Fish Eye’s gleeful pursuit of male targets while cross-dressing . . . or the sad yet poetic unrequited love Sailor Star Fighter/Seiya held for Sailor Moon/Usagi. I doubt most ’90s children found their own VHS mecca, and they were thusly denied such complexity and depth and liberating portrayals of loving relationships transcending rigid Western ideas of sexuality and gender. Perhaps that’s why coming out to my mother about my own sexuality never seemed unusual to me during my adolescence and why the introduction of trans and gender-nonconforming identities never raised my eyebrows.

Without these topics ever being a point of conflict or something earning much attention, Sailor Moon normalized that which American broadcasters never wanted me to see. And I’ll always be grateful to my childhood hero for that.