The button on the telephone base glows orange-red under my finger, an ember in the otherwise lightless living room: Do not disturb. To be safe, I stifle the glare with a piece of blank paper from the printer next to it.

I’ve already spent at least ten minutes distraction-proofing the rest of the room: drawing the curtains, dusting the TV screen, clearing the stand of clutter. My Wednesday evening routine without fail.

Finally, I settle onto the couch and carefully lay a blanket across my lap before turning on the TV. As the glorious light fills my carefully constructed darkness and the noise fills the silence, I sit with a pious rigor and wait until the top of the hour.

My sermons are in high-definition, delivered to me two million pixels per frame.

If The X-Files was my television baptism, Lost was my confirmation. From the pilot to the series finale, I watched every episode live, something I take more pride in than I probably should. I’d arrange my week around the show, canceling plans when necessary and living on online forums until the next new episode. In college, I even let a cockroach crawl on my bedpost until a commercial break so I wouldn’t miss a second.

Lost first aired around the time my parents got a divorce. It was a strange, confusing few years, as it is for any child who has to go through something similar. I felt an amalgamation of competing emotions, all of which ultimately made me feel disconnected and displaced in life. I didn’t know how to talk about it with friends, or if I even should — so instead, like most other things, I kept it to myself. I was also just entering high school, and with my best friend attending a different school than me, I had to find an all-new friend group. As the nerdy, overweight kid who only got in trouble for reading during class, that didn’t exactly come easily.

So instead, I developed a kinship with the characters onscreen.

Lost quickly became my personal outlet, something I selfishly felt entitled to: mine. I didn’t just relate to protagonist Jack’s personal demons and daddy issues. Every character on the island struggled with being existentially (as well as physically) “lost,” and I embraced each of their stories, using them to better help me understand myself. I hadn’t experienced anything as relatable and entertaining before, something so aligned with my own tastes and interests; I clung to it.

The Lost pilot remains something of an enigma. It boasted a whopping fourteen-person regular cast (and, for a network show, an extremely diverse one at that, rivaled only maybe by Grey’s Anatomy—bless ABC). At the time it aired, it was also the most expensive pilot in TV history, costing somewhere between ten and fourteen million dollars. On top of all that, it presented several potentially sci-fi mysteries, a bold move for a network television pilot. The combination of the above set up Lost to be the biggest flop in TV history—but something about its confidence and cliffhangers made millions of people, including me, keep tuning in, making it an instant worldwide phenomenon.

My sermons are in high-definition, delivered to me two million pixels per frame.

Throughout the show’s history, many TV critics have lambasted its lack of direction and countless mysteries, and while they’re not necessarily wrong, they might not have taken into account the show’s circumstances. Due to its whopping overnight success, the writers had to extend mysteries past their prime to keep viewers hooked, and as a network show in a pre-Netflix era, it had to carry the weight of twenty-three-episode unbingeable seasons. It makes perfect sense that after Lost premiered to such high ratings co-showrunner Damon Lindelof “pretty much wanted to die” at the nervousness he felt moving forward. How could he and his team sustain such a serialized plot without the time, budget, or freedom afforded to cable shows?

Of course they made stuff up as they went along—that’s the very nature of network television.

But finally, in the middle of the show’s third season, ABC did something unprecedented: It agreed to let the show end after three more truncated seasons. Unlike almost any other network TV show in the history of ever, Lost was afforded the opportunity to end on its writers’ terms.

So when it did, with a three-years-in-the-making denouement free of network restraints, free of cancellation fears, and free of filler episodes . . . why did most fans and critics absolutely hate it?

I’m standing inside a cemetery inside a Barnes & Noble—or at least, as I read the opening pages of George Saunders’ debut novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, it feels like I am. I’ve waited literal years for this book by my favorite writer, and I’m immediately invested after the first ten pages. The problem? I’m seeing him read the next night, and my ticket to the event comes with a copy of the book.

Instead of just waiting twenty-four hours to continue reading, I do what any self-respecting book-obsessed person would do: I buy another copy and stay up until 4 a.m. to finish it.

A scene from the “Lincoln in the Bardo” VR tie-in. (Image: Matthew Niederhauser/Sensorium)

The novel (if it could even be called that) contains elements of surreal historical fiction (if it could even be boiled down to a “genre”). It’s set in the cemetery where Lincoln’s son Willie is buried and told from the perspective of the “souls” of the dead there, who enviously watch as Lincoln cradles his son’s body each night. But in this narrative universe Saunders has carefully crafted, the dead don’t realize they’re dead—as the title suggests, they’re stuck in a transitional state, or bardo, between death and the next life.

Before reading Lincoln in the Bardo, my knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism was limited to other media. Salinger’s Franny & Zooey, for example, which uses allusions to Tibetan Buddhism as more of a literary device than a construct, or Gaspar Noé’s 2009 film Enter the Void, which turns it into a half-baked drug trip and person with epilepsy’s worst nightmare. My interest in the subject had been piqued but not enough to research further—I was young and, to be embarrassingly honest, fully subscribed to a Palahniukian nihilism. Life is just a long party that ultimately ends in a meaningless death.

And then someone I knew from my college writing program died of an overdose.

And then my grandpa was admitted to the hospital, where he’s suffered for the better part of a year.

And then a close friend my age was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Unlike Chuck Palahniuk, whose father was murdered in 1999 and whose grandfather murdered his grandmother before turning the gun on himself, I had no personal relationship with death prior to this past year. My “nihilism” was manufactured and misguided; it could afford to be.

For this reason, Lincoln in the Bardo arrived at a perfect time. It dealt with death in such a specific and beautiful way that I felt compelled to learn more about the ideas at its core. I put aside my nihilistic intentions for a moment and opened my mind to new perspectives and beliefs, researching and reading about karma, meditation, and of course, bardos.

I was young and, to be embarrassingly honest, fully subscribed to a Palahniukian nihilism.

The idea of the bardo comes from the Tibetan text Bardo Tödrol Chenmo. In English, a close translation is Great Liberation Through Hearing in the Bardo, as much of the text is meant to be read aloud to someone who is dying, but when the American scholar W.Y. Evans-Wentz first translated it in 1927, he titled it The Tibetan Book of the Dead (probably because, let’s be real, it sounded way catchier).1

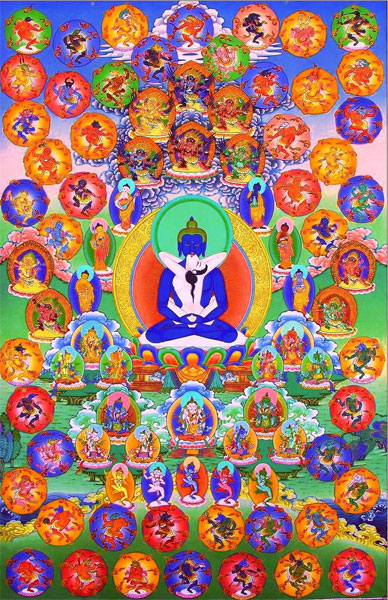

In Tibetan Buddhism, more bardos exist than just the state immediately before rebirth, referred to as the karmic bardo of becoming. The bardo of becoming is preceded by the natural bardo of this life, which can include two additional bardos of sleep/dreams and meditation;2 the painful bardo of dying; and the luminous bardo of dharmata.1 It’s this third bardo, the bardo of dharmata, where Saunders places his characters.

The one hundred peaceful and wrathful deities. (Image: VajraWheel.org)

Sogyal Rinpoche, in his book The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, organizes the experiences of the bardo of dharmata into four phases: luminosity, union, wisdom, and spontaneous presence. He states that only master practitioners in Tögal (“direct crossing”) will be able to gain liberation during phase one, luminosity; most people won’t be able to stabilize the experience—which is said to include blinding light and vibrant sounds and colors—or recognize that “these radiant manifestations of light have no existence separate from the nature of mind.”1

For Tögal newbies, this phase will pass instantly, without them even realizing.

These as-yet unenlightened many who pass into phase two, union, will then see small balls of light called tiklé manifest themselves and appear as deities (forty-two peaceful, fifty-eight wrathful, because of course even the intermediate state can’t be easy). In Lincoln in the Bardo, these deities manifest as people the dead know, there either to haunt them or help them become liberated. Once liberated, the dead disappear in a blinding light of their own, but Saunders cleverly creates conflict by not allowing his two main characters, Hans Vollman and Thomas Bevins II, to attain such enlightenment so easily. It’s only after they help young Willie achieve

such liberation by “uniting” him with his still-alive dad, Lincoln, in the novel’s spectacular climax do they realize they, too, are dead and remember their past lives while attaining enlightenment. This moment unites the final two phases of the bardo of dharmata, wisdom and spontaneous presence (and yes, I may have cried . . . a little).

Although Saunders, a Buddhist himself, is certainly not the first to tell a story inspired by The Tibetan Book of the Dead or Buddhist teachings, he does tell one that’s not only overt in its Tibetan Buddhist influence but, from the little I’ve researched at least, quite accurate as well. Unlike Franny & Zooey or Enter the Void, Lincoln in the Bardo shows deference to the teachings while still bringing them into the pop-cultural sphere.

And seven years before, in its divisive series finale, Lost did the same thing.

They were dead the whole time.

Ask any casual Lost viewer what they think happened in the series finale, and they’ll likely say the characters died in a plane crash and have been in purgatory for all six seasons.

Other, more astute viewers might say, “No, I understood it. They were only in purgatory during season six. But I still hated it.”

Trying to change someone’s thoughts on the finale is a Sisyphean task. It’s not very fun, and it’s even less easy, but frankly, it shouldn’t be a task at all because everyone is entitled to their own opinion. Maybe because I cherish the final episode (aptly titled “The End”) so much, I continue challenging people’s beliefs. I attempt to explain what actually happened in the final ten minutes to those who didn’t quite understand or reason with others who thought hundreds of mysteries went unanswered (with a little bit of inference, you can actually find answers to nearly everything). But with each defensive exchange, I’m reminded of why I loved “The End” to begin with and why, even as something of an agnostic nihilist, the more spiritual elements resonated so well with me.

In its final season, Lost introduces viewers to a new storytelling technique unofficially dubbed “flash-sideways” (to align with its earlier uses of “flashbacks” and “flashforwards”). After a bomb is detonated in the time-travely season-five finale, it’s implied that it somehow created this so-called flash-sideways universe, in which the characters’ plane lands safely at LAX and they live out slightly different lives than what we’ve seen in past flashbacks. Throughout the season, flash-sideways scenes are interspersed with the continuing island A-plots and unexplained until the final moments of the show. In those final moments, set in a church, the main character’s previously dead dad appears, delivering the only explanation of the flash-sideways provided:

Jack Shephard: Are you real?

Christian Shephard: I sure hope so. Yeah, I’m real. You’re real. Everything that’s happened to you is real. All those people in the church, they’re all real too.

JS: No. They’re all . . . they’re all dead. I’m dead. You’re dead.

CS: Everyone dies sometime, kiddo. Some of them before you, some . . . long after you.

JS: But why are they all here now?

CS: Well, there is no “now” here.

JS: Where are we, Dad?

CS: This is a place that you . . . that you all made together so that you could find one another. The most important part of your life was the time that you spent with these people on that island. That’s why all of you are here. Nobody does it alone, Jack. You needed all of them, and they needed you.

JS: For what?

CS: To remember. And to . . . let go.

JS: Kate. She said we were leaving.

CS: Not leaving. No. Moving on.

JS: Where are we going?

CS: Let’s go find out.

Jack then reunites with the characters we’ve come to love after six seasons before all “move on” together in a flash of bright light, juxtaposed against Jack’s present death on the island.

It was immediately clear to me from Christian’s monologue that everything on the island had really happened, and this flash-sideways place, whatever it was, existed so the characters could “move on” together.

Despite the seemingly heavy-handed religious overtones, the show never truly subscribes to any one belief, which is why it never bothered me. There’s even a stained-glass window in the flash-sideways church that features six different spiritual symbols, implying it’s a place meant for people of any or no religious affiliation. Not to mention the thing no one seems to bring up when talking about the finale: the fantastic island story, which takes up the bulk of the episode and is seeped in so much sci-fi mythology, Star Wars references, and epic battles, it well outweighs the more emotional, spiritual conclusion.

Jack approaches his father’s empty coffin in the flash-sideways. (Image: ABC Studios)

In “The End,” the show means something different to everyone: a scientific character-driven story rooted in deep sci-fi mythology, a spiritual examination of the human condition, or, for some, yes, a six-year long con. To me, it was always a story about people—identity, friendships, love, unity. As Jack says in season one, “If we can’t live together, we’re going to die alone.” Sure, the mysteries are what got me on the forums and appealed to my inner geek, but I laughed and cried because of the characters; they made me feel less alone and taught me to value my real-life friendships.

They made me happier to be alive.

A few days after the finale aired, I watched it with my mom. We cried together (me, for the fourth time already) and celebrated by going out to dinner afterward. At the restaurant, I asked what she thought of it, how she felt. Immediately she started talking about her friend Sue who had died that same month. My mom never really had many close friends; Sue was one of the few from high school who was still alive. The others, with whom she had been in and out of contact for years, had experienced domestic abuse, drug addiction, and cancer. I only had a vague idea of who these people were from stories and hazy childhood memories, but despite not seeing these people for years, the news of their deaths still had a profound impact on my mom — they were no less important to her now than they were over thirty years ago.

I laughed and cried because of the characters; they made me feel less alone and taught me to value my real-life friendships.

Because of this conversation, because of the emotions I felt watching and rewatching the week it aired, the growing backlash surrounding the finale saddened me. I wished everyone I’d talked to about the show and theorized with for years had connected to it in a similar way, but alas, I’d more often than not always be the odd one out.

Whenever I revisit that final scene, either during a rewatch or just in my head before I fall asleep (because I’m a nerdy, Lost-obsessed weirdo), my interpretation slightly changes. Considered by most to be a total copout and a huge factor in their dislike of the finale, the deliberately vague explanation for the flash-sideways universe fascinates me. For fun, I’ll create different explanations for its existence in my head—some scientific, some more abstract—until I think of one that I find most exciting or that aligns closely with my beliefs.

Finally, shortly after finishing Lincoln in the Bardo, I landed on the one to outdo them all.

According to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the Ground Luminosity (or “Clear Light”) dawns at the time of our death. Like night turning into day, the Ground Luminosity materializes as brilliant light, where “mind unfolds from its purest state.”1 Experienced practitioners can immediately identify the Ground Luminosity and become liberated from samsara, or the cycle of death and rebirth, but most, like the characters in Lincoln in the Bardo, will instead pass into the bardo of dharmata. Here, it may look like the world we’ve left behind, but the challenge is to understand it as just an extension of the nature of our mind. Only then can we attain enlightenment.

The dharmachakra. (Image: Shutterstock)

Like the cemetery setting of Saunders’ novel, the flash-sideways universe in Lost is a kind of bardo of dharmata in which the characters don’t know they’re dead. Only when they realize it’s the energy of the nature of their minds—the Ground Luminosity—and embrace who they became during and after their time on the island do they have an individual awakening that allows them to then be liberated together as a group.

It makes perfect sense, considering the Buddhist influences present in Lost since its inception: Dharma, as in the fictional DHARMA Initiative company at the center of the show, means “the basic principles of cosmic or individual existence” in Buddhism. And the giant wheel Ben turns in the Orchid station at the end of season four, moving the island through time? It very closely resembles the dharmachakra, or “Wheel of the Dharma,” a symbol commonly used to represent Buddhism and one of the six symbols on the stained-glass window in “The End.”

Perhaps most exciting is the Source at the Heart of the Island, a cave of bright, warm light described by the island’s first known protector as “life, death, and rebirth”—a physical manifestation of samsara. In “The End,” the characters must fight to keep the Source alive, otherwise the island will sink and put out “the light” everywhere in the world and inside every person. It makes sense too that the island is already underwater in the flash-sideways bardo, its Source seemingly extinguished. As Christian states, “There is no ‘now’ here”; when they become liberated and the church fills with the bright light, it can be interpreted as the Source returning.

On the island, they must protect the Source to save the world; in the bardo, they must reclaim the Source to save themselves.

Ben Linus turning the “frozen donkey wheel” and unsticking the island in time. (Image: ABC Studios)

Of course, if this analysis is to be believed, the show takes some creative liberties in its depiction of the bardo. Instead of forty-eight peaceful and fifty-two wrathful deities, we only really get Desmond, who goes around hitting people with cars and punching them senseless in an effort to get them to remember. We also get characters like Eloise and Ben, who are fully awakened and remember their pasts but have the ability to choose not to move on with the others. Lastly, Christian says it’s a place they all made together. Because none of the characters were practicing Buddhists as far as we knew, could that mean the detonated H-bomb at the end of season five somehow still helped in the creation of the bardo? Again, much is up to interpretation and can be explained away scientifically, spiritually, or magically, depending on what you want it to be—but it’s interesting (and smart) how Lost creates a bardo that follows its own rules, entrenched more in the show’s own mythology rather than being a carbon copy of the Tibetan Buddhist bardo of dharmata.

In this way, much like Lincoln and the other media I’ve mentioned, Lost Westernizes the Buddhist teachings and adjusts them to fit its own narrative. While that may seem icky, it’s nothing new; we’ve told countless Jesus narratives over decades, both subjugating and reinforcing religious ideas through themes, motifs, and symbolism. Personally, I’m happy to finally see a rise in Eastern influence. Good art should challenge people’s beliefs while also connecting on some kind of emotional level, and Lincoln and Lost do both in spades while still treating the source inspiration with respect.

Because these books, movies, and films include lesser-known Eastern concepts (theological and otherwise), I was exposed to new ways of thinking that helped me cope with the idea of close friends and family dying. While I have only a surface-level understanding of some Buddhist concepts and no plans to practice it religiously, I’m thankful for its inclusion in some of my favorite things in pop culture of the past decade—it made for a richer, more cathartic reading and viewing experience I’ll continue to cherish for years.

But for now, I’m going to dust the TV, clean the stand, and turn off my phone. I’m going to make my living room as dark as a cave and sit on the couch curled up under a blanket. I’m going to grab the remote, place my finger over the “on” button, and take a deep breath.

And then, when I’m ready, I’m going to let the bright light take me somewhere new.

1Rinpocbe, Sogyal. The Tibetan book of living and dying. Beijing: Zhejiang U Press, 2011. Print.

1Rinpocbe, Sogyal. The Tibetan book of living and dying. Beijing: Zhejiang U Press, 2011. Print.

2Karma-gliṅ-pa, Francesca Fremantle, and Chögyam Trungpa. The Tibetan book of the dead: the great liberation through hearing in the Bardo. Berkeley: Shambhala, 1975. Print.