In 2015, on the night before my twenty-fourth birthday, I took my seat in the front row of Cherry Lane Theatre in the West Village with three of my closest friends. We were there to see Homecoming King, the one-man show by Hasan Minhaj (then only of The Daily Show fame). The majority of the audience resembled us: young Indian-Americans, some with friends and some with parents, excited to see Minhaj portray the stories of his life in front of us.

When the show started, I found myself often locking eyes with Minhaj himself during moments of great tension and emotion: I was there with him as he crashed his sister’s bike and relived his Pizza Hut commercial glory days and when he felt the first pangs of lust in his high school math class. Minhaj danced from one side of the stage to the other, using projected visuals sparingly and for maximum impact, easily transforming his immigrant stories into all of our stories. To say it was immersive is to sell it short; I had never seen anything like it.

Audiences across the world now know how delicately Minhaj is able to switch from hilarious to heartbreaking thanks to the Netflix comedy special of the same name. Premiering earlier this year, the special features a taped version of the show I got to see two years ago and manages to capture the intimacy of that small room on camera. One of the hallmarks of Minhaj’s performance is his expressiveness—the way his eyes widen, how he generously shows his excitement like a kid in a candy store. With his rapid pop culture references and confident swagger, Minhaj is an East Coast darling and a California bro all at once, and in that he’s someone we all know. His passion is palpable, and the filmed version of Homecoming King leans into this strength with its wide camera angles and close-up shots just as the storytelling reaches its climax.

It’s no surprise to readers now that I’m the daughter of immigrants—and a proud one at that. But before Homecoming King, I never had a piece of entertainment I could point to as coming close to my story. Much has been written about immigrants chasing the American Dream, often focusing on the generational clash between those who did the actual immigration and those who are simply benefiting from it. In the South Asian lens, those contemporary differences usually manifest in professions and relationships. As Minhaj weaved tales of heartbreak at the hands of covert racism or seeing his artistic career reach new heights, I found myself empathizing and identifying with his stories, even though they weren’t the same experiences I had endured.

My childhood was easy. Despite living in suburbia in the Midwest, I don’t have memories of bullying or racism, especially after 9/11. But when Minhaj talks about the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, he talks about actual physical threats to the well-being of his family. Perhaps I was too young to have fully understood the slips of backhanded comments or the discreet looks of disdain my parents may have noticed; I was, after all, only ten years old when the attacks shook our nation. But I felt a shift after the 2016 election, and I have had overtly racist comments slung in my direction in the months since November (in New York City nonetheless).

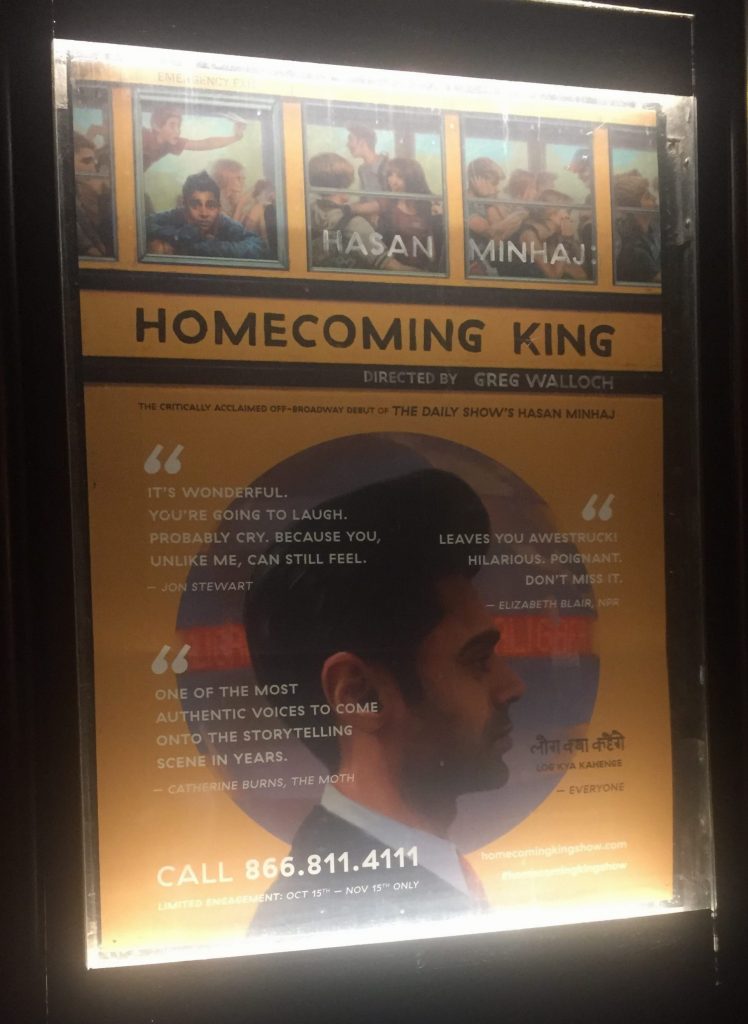

Image: Netflix

It’s no secret that white supremacists and racists have become emboldened since the election, but this problem isn’t new. Our nation has long held discriminatory latencies, and Minhaj doesn’t shy away from expounding on what it has been like for a person of color in this country for years. Watching Homecoming King in 2017 was an entirely different experience than it was when I first saw it in 2015.

In a climate where we feel as divided as ever, I’m thankful for pieces of culture such as Homecoming King that humanize varied experiences by making them approachable and relatable to everyone. One of the most lasting impacts of Minhaj’s special is how easy it is not just to understand his stories but really feel and experience them alongside him. We need more of this from people of color, from marginalized groups, from people whose voices are being silenced by the hateful policies of this administration. In 2017, more than ever before, we need art and culture to show us the light and pave the way toward a more inclusive nation.

I’m thankful that Minhaj had the audacity to tell his story, that he proudly portrayed Muslims and South Asians as caring, flawed, complex individuals—as every single living, breathing human being is. I’ll never forget what it was like to be in that theatre, seeing a brown person confronting racism and enjoying professional success, feeling joy and heartbreak in the same breath. And now I don’t have to rely on just the memories; I can rewatch it whenever I want.