As a writer who writes horror, it’s often hard for me to find ways to get reinspired on the small screen, mostly because, well, let’s admit it: Horror isn’t family-friendly. And for a writer who is interested in graphic grotesque, that search becomes harder.

So it was fate I would discover Hannibal, a three-season series that came to a tenuous, unsure end in August 2015. This does mean it could be brought back, as fans will always rumor. And, yes, it is the Hannibal Lecter you love (but portrayed by Mads Mikkelsen, not Anthony Hopkins).

I was immediately brought in not only by my favorite fictional serial killer but by the aesthetic risks the show took. It is one of the few television shows I’ve ever seen keep a consistent body horror theme to the images.

What is body horror? If you’ve never seen the anime Parasyte, think about films directed by David Cronenberg; corresponding imagery to NIN, Skinny Puppy, Throbbing Gristle, and other Industrial acts; splatterpunk; classic anime Akira; the Hellraiser film series; Cannibal Holocaust; Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom; In the Realm of the Senses; Begotten . . . and, on the other end of the spectrum, the Hostel, Saw, and Human Centipede series. (Don’t watch those, though.)

What struck me about this show was the eroticism of the deeply disturbing images of violence we encounter. It lent itself deeply to the overarching themes of Thanatos (destroyer nature that mirrors erotic nature in Freud’s theories of psychoanalysis) and proved a provocative vehicle for Hannibal’s erotic, but not always sexual domination, over Will Graham and others.

The show ultimately gives way to eroticism of domination and control, whether physical, mental, sexual, or emotional, all through excruciatingly artistic visions of violence.

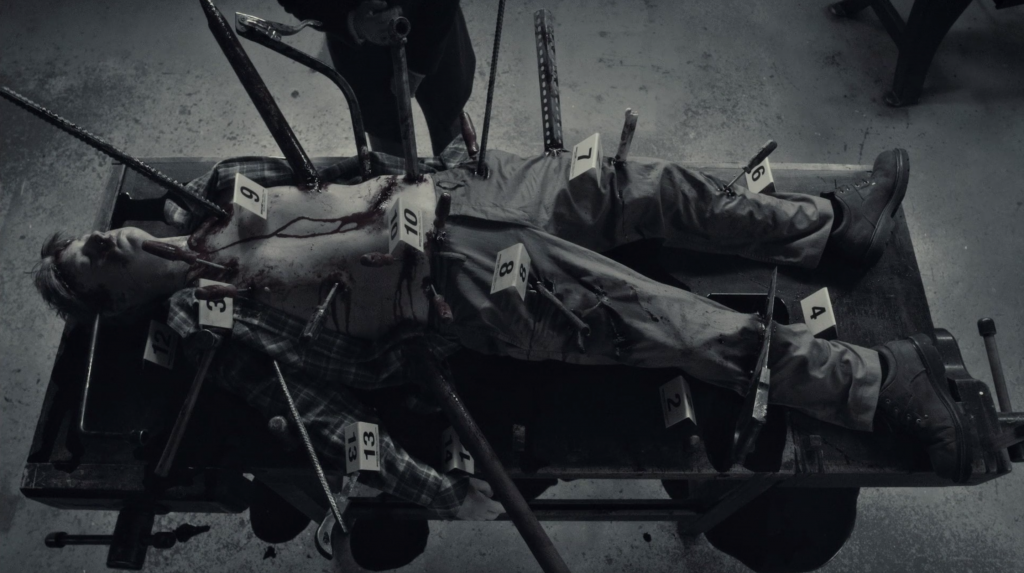

Image: Amazon Prime Video

The first artistically displayed body we see is a young woman mounted on a dead buck, her body pierced and mounted on its antlers. It’s a shocking sight, but as it turns out, she’s not the victim of the killer who Will Graham, Hannibal, and the rest are chasing; it’s a copycat.

Her body looks like something between artsy pornography, brutalist nature photography, and surrealist art. We stop eroticizing her, and continue to. We’re supposed to feel disgusted.

Her lungs are missing.

The lungs are prepared as a meal at the enigmatic Hannibal Lecter’s kitchen as he enjoys classical music. Hannibal’s cooking is always marked by a piece of classical music, which shows off his callousness for his dietary habits and his mad cooking skills. Close-ups of the processes of cooking perpetuate the series.

A word about these interludes: They whet appetites. They are designed to inspire hunger. We’re talking food-porn images. But we’re struck by how this should disgust us because we are seeing the human meat through the connoisseur cannibal’s eyes.

The girl on the antlers isn’t the only beautiful/creepy corpse we encounter; it’s just the first.

A garden of diabetic patients making a mushroom garden grow. Viking blood angels. A man’s corpse stuffed with poisonous flowers. A cellist posed to play the cello that’s been slammed through his throat. A man with a honeycomb in his skull. A totem pole of torsos. A spiral of bodies in a color spectrum. A body with wounds resembling Wound Man. A woman with a Glasgow smile. A man with a Colombian necktie. A woman catching fire in an iron lung. A woman’s body, cut with a butcher’s saw into thin slices, preserved under glass, displayed vertically. A man with his face torn off by hogs. A man folded up into the shape of an anatomic heart. Two men removing prosthetics to reveal their wilted faces. A man on the end of a rope, then his disemboweled guts tumbling to earth. A pig pregnant with a human fetus. A naked man with a full tattoo of William Blake’s Great Red Dragon on his back as he exercises rigorously. A suburban house completely splattered with blood impacts. A family with mirrors inserted into their eyes and genital sockets. A man in a wheelchair set on fire. The same man alive with many layers of his dermis burned off. A three-way bloodbath as three men knife-fight it out on a seaside terrace.

And these are just images of events occurring in the series, not including the vivid dreams Will Graham has.

Image: Amazon Prime Video

If you don’t think you know what these images look like, you might be surprised. They take their inspiration from the Hellraiser series; from the art of H.R. Giger, Edvard Munch, William Blake, Henry Fuseli, Francis Bacon, and Pablo Picasso; from the famed Uffizi Gallery of artwork; from the photography of Man Ray; from the Elizabeth Short, or “Black Dahlia,” case file; from Weegee’s crime photos and other mafia-era photos; from 17th-century alchemical texts; from Gray’s Anatomy (the textbook) and da Vinci’s medical drawings; from Stan Brakhage’s film Autopsy; from ethnic art; from wartime photos of both World Wars and Vietnam; and from BDSM and industrial fetish art.

We do not see these associations objectively in the images. They are like stream-of-consciousness associations, as though we are on Lecter’s couch. Hannibal is in our heads as we progress from one gory scene to another. We know he’s the copycat killer. We’re a voyeur at the scene of an accident, even a fictionalized accident . . . We don’t want to look at a gory roadside slaughter, rubbernecking, but we can’t stop.

We also know Hannibal is a great psychiatrist, sociable, elegant, intelligent, refined, doting to those he cares for, scathing in a bourgeoisie style, a skilled artist and musician, and probably a great gourmet chef. Physically, he’s strong and fit despite his age, an asset we see him use during his assaults, but he’s decidedly visually appealing. But as his veneer unravels at times, we wonder if his polished charms are manipulations masking the stag wendigo creature Will Graham hallucinates.

Hannibal Lecter is a multifaceted character so perverse and complex it’s hard to dispute how much the audience is supposed to desire him, hard to put a finger on why, but we’re not alone. All the characters in this show create nuanced sexual tension between each other.

Even in his professional life, Hannibal seems to relate to others with dominance in mind.

The Red Dragon, or “Tooth Fairy,” birth name Francis Dolarhyde, an imposing man with a physique that either borders on the classical or the grotesque (or both), is the character most aware of Lecter’s erotic magnetism. When the two speak on the phone (Lecter from inside a posh glass cell), Dolarhyde speaks clearly, awe in his voice. He momentarily overcomes his cleft palate speech impediment—celebrity worship has rendered it nonexistent. Dolarhyde and Lecter imagine each other (or is it just one or the other?) in Lecter’s original psychotherapy office, discussing how to do away with Will Graham and Dr. Chilton. Lecter doesn’t hesitate to use Dolarhyde for the last task he’d like to: his revenge on Chilton. But the cannibal doesn’t worship the Dragon the way the Dragon worships him, so ultimately, he’s manipulating Dolarhyde for his own means. His lack of verve for the man’s “work” is evident; however, for his own benefit, he leads Dolarhyde on. But Lecter doesn’t let him threaten a more tantalizing target.

Hannibal has his own therapist, Bedelia Du Maurier (Gillian Anderson), in whom he confides and to whom he confesses. Their sessions are unorthodox; they drink together during the session. She ultimately becomes his prisoner, kept so under a cornucopia of drugs, part of his alibi and disguise as he hides in Europe. She has a full episode of Patty Hearst–style Stockholm syndrome while with him. Romantic.

Hannibal has a sexual relationship with consultant profiler Dr. Alana Bloom (Caroline Dhavernas), and the episode they have sex in you’ll want to watch no matter your sexual orientation—it’s just that artsy. However, Hannibal attempts to later silence her by pushing her out a window. Bloom almost had a relationship with Will Graham, but she can’t reciprocate his feelings. Alana Bloom ends up with Margot Verger (Katharine Isabelle), but that’s a twist that would require too much explanation. Just rest assured, also, that the sex scene between these two rivals that of the one previously mentioned. Margot also almost had Will Graham’s baby, despite being a lesbian. (This gets complicated quickly.)

Hannibal has a paternal relationship with Abigail Hobbs (Kacey Rohl), the daughter of the original killer, but he has control over her. Because she’s being hunted by the FBI, she cannot leave his home. She eats food he prepares, wears clothes he provides, hides when others visit the swank therapist’s home. The characters’ body language indicates a deep power dynamic is involved, even if it is not overtly sexual.

Even in his professional life, Hannibal seems to relate to others with dominance in mind. He interacts frequently with Dr. Frederick Chilton, who runs the Baltimore Hospital for the Criminally Insane, who also seems to have a penchant for aggressive communication styles. Hannibal always gets the last word in on Chilton. This relationship becomes even more heated as Hannibal finds it necessary to frame Chilton as the murderer. Later, Hannibal gives Francis Dolarhyde Chilton’s home address and doesn’t seem displeased when Chilton ends up with several layers of his dermis burned off.

Image: Amazon Prime Video

His most explicit sadistic relationship is with Abel Gideon (Eddie Izzard). For foiling Lecter’s perfect plans, Abel’s forced to eat his own flesh while he is kept on medical support. Meanwhile, what remains of his limbs is fed to snails. The snails are a delicacy, one Hannibal likes and consumes and encourages Abel to consume too. Abel is fed a diet of sweet ingredients to make his flesh, and the snails, taste better. It’s a slow, extended, horrible death. For Hannibal Lecter, manners count, and interfering in his plans is unmannerly.

He has a more short-lived sadistic relationship with Mason Verger (first played by Michael Pitt in season two, then by Joe Anderson in season three). Mason Verger is as a multimillionaire pedophile who sexually assaults his lesbian sister. Lecter drugs Verger with a powerful form of MDMA and encourages him to scrape flesh off his own face and feed it to his prize hogs. Lecter completes the act by knocking Verger into the pen. It’s a grisly, alien sight. Mason’s face is destroyed though he is alive.

Sister abuse is something the cannibal cannot abide, but it has little to do with Margot.

Of course, this is all missing the origin story of the cannibal. Hannibal may or may not have actually consumed parts of his own dead sister. She was killed in a savage attack by a crazed Russian soldier occupying his native country of Lithuania. The soldier also attempted to eat his sister but was stopped before the act could begin. In fact, the accused soldier has been imprisoned in a makeshift cage in the Lecter home for decades, guarded by a loyal servant.

The sheer amount of psychological mindfuckery that goes on during the series is an indictment of psychiatry in general.

Why would Hannibal eat his murdered sister? This borders dangerously close to incest, where the then-teenage cannibal would have been introduced to the practice in a time of deep grief. Perhaps we’re close to the traditional ethnic meaning of cannibalism as a ritual of worship or deep togetherness. But overtly sexual overtones of the act cannot be missed. The fact that the cannibal has never gone back to Lithuania and is incapable of returning solidifies that he feels deep shame over the act. He knows the meal was a reflection of forbidden lust for her.

Probably. Speculation will get you anywhere.

But even this relationship is inferior to the one Hannibal has with Will Graham (Hugh Dancy). Hannibal’s relationship with Will works to extrapolate his entire nuanced character.

Who is Will Graham?

Well, he’s got an eidetic memory and has tons of empathy, meaning he can imagine so deeply that he can adopt the perspective of a killer, which is not good for him at all. He most likely is on the autism spectrum. He’s always depressed. He’s had symptoms of fugues, insomnia, hallucinations, and sleepwalking, which were all caused by a real physical disorder. He was gaslit. He’s had manipulative hypnosis, psychic driving, and abusive interrogation techniques used on him. He’s had knowledge of life-threatening disorders denied him, and he’s had life-threatening procedures postponed until the last moment. Hannibal and others led him to believe his symptoms of encephalitis were symptoms of a psychotic break. He’s been wrongfully imprisoned. He was stalked by news reporters, who got photographs of him in the hospital.

In short, he is a punching bag.

Psychologically, Will Graham never, ever rests or feels peace. He’s haunted by life he was forced to take. Once, out of desperation, he’s forced to use another sociopath to try to eliminate Lecter and uses his own powerful imagination to lure the man into his plot. He pursues Hannibal despite the fact that he knows Hannibal tried to set him up. They seem to never tire of this game, though both have clearly regretted playing.

Hannibal was Will’s therapist, was so deeply inside of Will’s head that he was able to pull the strings intimately, which maximizes the payload of pain he’s taking.

The sheer amount of psychological mindfuckery that goes on during the series is an indictment of psychiatry in general. Let’s be clear: Hannibal is a psychotherapist. He’s interested in working through a patient’s issues by all and any means necessary. He doesn’t want to drug Will’s problems away. Dr. Chilton, as much as we dislike him, has the same perspective and tries the same approach with Abel Gideon. Both doctors fail when they turn to abusive, controlling means to be correct in their theses. They use their authority to deprive patients of self-control and willpower.

But why does Will Graham receive Hannibal’s royal torture treatment? Hannibal’s other patient got a much cleaner, succinct end. Hannibal seems not to lack targets, so why him?

We feel Hannibal didn’t have a plan for Will the way he plans for others. Hannibal assesses their worth to him, uses them awhile, then disposes of them, with or without a meal—or, if he’s feeling merciful, sets them free, bewildered, with their lives.

Ultimately, this fascination, which can obsess the mind, is the crux of an erotic fascination, and perhaps supersedes it

Will fascinates Hannibal on a level that either defines or contradicts our traditional ideas of erotic fascination: Will engages Hannibal’s curiosity. This is high order, considering the cannibal’s breadth of intellectual and artistic abilities. Will feels the same. When asked, Will responds that he’s never known himself the way he knows himself with Hannibal. He later states that the two are conjoined; he feels himself to be one with Hannibal, to the point he believes Hannibal’s crimes to be his own.

Ultimately, this fascination, which can obsess the mind, is the crux of an erotic fascination, and perhaps supersedes it. Eros does not always lead to sex. The idea that it can be denied might be what keeps it interesting.

But are Hannibal and Will in love? The answer: Which “love” do you mean?

Hannibal’s attraction to Will could be, for example, compared to Dante’s longing for Beatrice. Dante’s pursuit of another man’s bride cannot ever be fulfilled, especially now that she is in the grave. That’s beside the point. The urge that can never be fulfilled is the one that summons Virgil to Dante in the first place. Hannibal’s a big fan of Dante, which is why he circulates back toward Florence. (Also, history buff alert: The creators did a clever tie-in with the series. Was Hannibal Lecter Il Mostro, the famed Monster of Florence, real-life unidentified serial killer who preyed on couples? You bet. Eat your heart out, Zodiac Killer, with Chianti and fava beans.)

All this ultimately circles back to sexuality. It’s funny that I’ve managed to make most of what I write about sexuality, not that I meant to. I don’t like giving people the wrong idea about my sexuality. I’ve had less of the real thing than most people I’ve met. My fascination is akin to that of medieval celibate monks who doodled erotic drawings in the margins of hand-copied illustrated bibles. But that’s more TMI than you want.

This series allows the characters to move freely between Eros and Thanatos freely, with each interaction toying with that division. It spills over each character like a plague, the wanting, needing, craving, desiring, taking with consent, taking without, consuming raw or cooked, gorging, discarding what can’t be taken, and regretting every mouthful of their desired objects they cannot claim for themselves.

These characters objectify and fetishize each other. A character desires another for whatever emotional, psychological, or sexual satisfaction they can gain and does not even consider the needs of their object. Or, worse, they pretend to care to make the pursuit more interesting.

This never ends well. This is where the ends of eroticism, taken too far, ultimately meet sadism: The minute we desire without considering others, they become objectified. Objects to be used, then discarded.

Image: Amazon Prime Video

What is impressive about this series is that it makes this perversion the baseline aesthetic; it does not hide the inherent psychological violence of objectification and fetishization but makes it central to the narrative. If Hannibal is a sadist, this is troubled by the fact that everyone in the series, on some level, engages in sadism (and accompanying masochism). The original desire for anyone can quickly descend into unreciprocated desires, addictions, and perversions. How we cope with them and the level to which we let them obsess us is what makes any eroticism a potential horror.

This is the dark center of the series: We want what we want. Wanting is human. Sometimes we don’t care if we’re reciprocated. It might be human to overindulge, dangerously. What Hannibal risks, and aesthetically achieves, is making the inherent violence of these intentions vivid, gory, and gratuitous while still keeping a true level of cultural and artistic class to it. It is unapologetic too. It doesn’t forgive such intentions and doesn’t normalize unrequited desires. It portrays it for what it is: something that can drive anyone over the edge if taken there.