I’ve loved zombie movies since I was a kid. They were a way of talking about the promised nuclear apocalypse without talking about it—the only way to talk about the biggest, most important things.

Dawn of the Dead—the original—was no doubt my favorite. I rented it again and again. I picked up the novelization and read it. I made sure all my friends saw it. The movie informed our conversations—what would be the best possible structure to reinforce, how would we do it, and how would we survive there. This was a favorite pastime of me and my childhood best friend, Joe Martin. We decided on the Greendale YMCA. It had a fence around it, and a lake adjacent. In hindsight, I think this was a mistake. But we planned on how to do it, through endless afternoons. Maybe we should have been planning for something other than the end of the world.

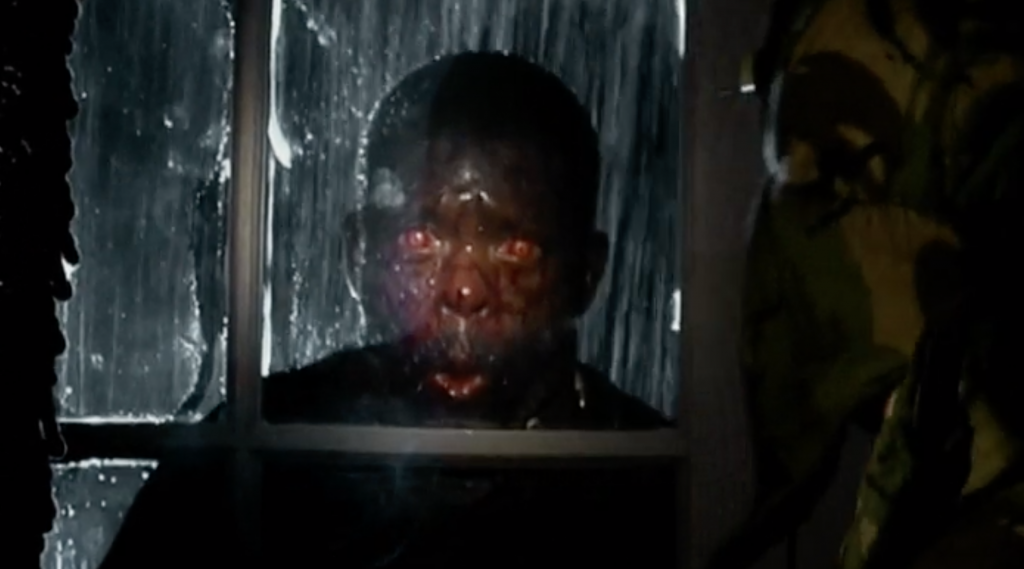

We argued and piled plans on plans, with each postapocalyptic solution making us better friends. The last movie we saw together was 28 Days Later. It was different—the idea was different. The zombies weren’t just the walking dead, animated by a hunger for human agency, also known as brains. They were angry. These zombies ran.

Image: DNA Films

That was 2002. The zombies have been running—arms flapping at their sides—ever since. A few years later, they redid Dawn of the Dead, all full of running zombies, and it was different from the original, but it was great. I remember watching it in the theater and later on DVD with a bottle of Maker’s Mark while working on my own apocalyptic novel The Last Bad Job (now available as an audiobook wherever you might imagine). In 2007, Joe Martin was shot dead in a bar fight.

When The Walking Dead came out, I gave it a shot. But the long scenes of undeveloped characters dramatically mourning the death of even less developed characters seemed like the kind of half-clever pretentiousness that has turned every schlock genre into a self-serious but-imagine-how-alone-Superman-must-feel shitfest, from Christian Bale Batman until the if-Ant-Man-can-change-then-we-all-can horseshit of today.

I was born in 1977 and lived most of my young imaginative life in the expectation of nuclear war. And that’s in which I watched the VHS copy of Night of the Living Dead that I got out of the library when I was eleven or twelve. And it all made sense, as did my loss of interest in the genre after the early ’90s.

But the idea of zombies didn’t originate in the Cold War. The term itself is older. First recorded in the 1810s in Haiti, it’s most often associated with voodoo, exotic poisons, and so on. I don’t claim to be an expert. Then, as part of my research for a new book whose plot hinges on the emergence of an ageless variety of debenture, I was reading David Graeber’s Debt: The First 5,000 Years. And he had this to say about zombies and the culture that gave birth to them. “Tiv (a people in Africa) horror stories about men who are dead and who do not know it or men who are brought back from the grave to serve their murderers, and Haitian zombie stories, all seem to play on this essential horror of slavery: the fact that it’s a kind of living death.” This was embedded in a millennia-spanning section about how a slave had no actionable relationships with anyone but their master and how they had been extracted from their social realm and thus been made socially powerless—dead. The book is a real wonder, whether you’re a surly teenager or a C-level joker wondering how, exactly, to land this plane.

But what struck me was the idea of men who are brought back from the grave to serve their murderers, which brought me back to zombies.

It reminded me of how someone can have their identity stolen. To anyone with a private, well-developed sense of who they are, the notion of identity theft seems a little ridiculous at first. What’s hard to acknowledge is that there’s another social identity we create via our actions that can act on its own. What’s harder to entertain is the notion of an identity constructed via surveillance, then bought and sold. But the creation and sale of these surveillance-driven data-zombies appears to have become the fastest-growing part of the national economy over the last decade. The assembling and owning zombies are apparently why journalism had to be put to the torch, why social media is a constant stream of provocations, why Amazon will sell junk at a loss, why it seems all too likely that your phone is tracking not only your movements but your conversations.

Image: AMC

Those data-zombies extracted from us inform the design of the world more than we do. Blind, pulling at you with shoe ads, they function in the service of our own manipulation. En masse, they crowd the doors. You can outrun them, but unlike you, they never sleep and never doubt.

They will take this essay and turn it to more dead flesh swaying down the street. There is something unstoppable about zombies. No matter how many you kill, the dead will always outnumber the living, not unlike how the petabytes of uncomprehending copy-and-paste information proliferates every day beyond our ability to scan.

It’s a bite that does it—the penetration and separation of meat from a living whole body into an alien digestive system. Maybe, at the point where the teeth snap the surface of the skin, you hear a sound like a click. From there, an alien digestion takes place—like the movement from a familiar, human existence with firm personalities to the go-with-the-flow-to-god-only-knows of the market.

As I get older, I approach the objects of imagination in new ways, increasingly sympathetic to the villains. “Can you imagine what Darth Vader’s health insurance must be? No wonder he works for the Empire.” That kind of thing. It’s easier to be backed into a corner than to start a fight with the logic of my neighbors or of a billion-dollar industry. And some corners, when you get backed into them, have comfy chairs and snacks.

It’s easy to be a zombie. They’re everywhere, and always biting. But while zombies may overrun the earth, they never win. They’re a miserable lot. Part of what they are is not relatable. They seem to know as much. What they want is to make more zombies. They want you to live exclusively by the same simple dictates that they do. They want you to do what they do: find working minds and devour them with your mouth.

Siding with the zombies is a cynical move, and it won’t save you. Death is certain; it doesn’t need volunteers. The zombies are at the door; they fill the streets. I’ve seen enough of these movies to know that a shotgun holds only the promise of more of the same.

So let’s do the hard thing and seriously consider what being alive might be.