Don’t let its title deceive you: Devilman Crybaby is an unflinchingly human story. From director and animator Masaaki Yuasa (Kaiba, Adventure Time), the series is Netflix’s latest (and greatest?) foray into original anime programming. Fresh off the heels of 2017’s other successful Netflix anime originals, including the video game–inspired Castlevania and Vampire Weekend frontman Ezra Koenig–created Neo Yokio, the show joins over fifty total anime shows currently available on Netflix, but it’s the first of many originals to join the streaming giant’s 2018 lineup. (Four series alone are set to arrive in March 2018, with Netflix actively working on a whopping thirty total.)

The series follows high schooler Akira Fudo, who becomes a “devilman” after his friend Ryo Asuka incites the demon Amon to merge with Akira during a drug-fueled satanic orgy. And if just that premise already sounds like a lot, you don’t know the half of it. (Warning: Major spoilers ahead.)

Because of Akira’s deep empathy (he cries whenever he senses another person is sad), he’s able to maintain the heart of a human and the body of a demon—a literal devilman crybaby. This allows him to kill other demons who are hurting humans. But Ryo is (no pun intended) hellbent on exposing the demons’ existence to the world and protecting Akira’s identity at any cost. “Love doesn’t exist,” he says. “There is no such thing as love. Therefore, there’s no sorrow.” It seems like for every demon killed and human saved by Akira, Ryo is putting more humans in danger, if not straight-up killing them himself.

Image: Netflix

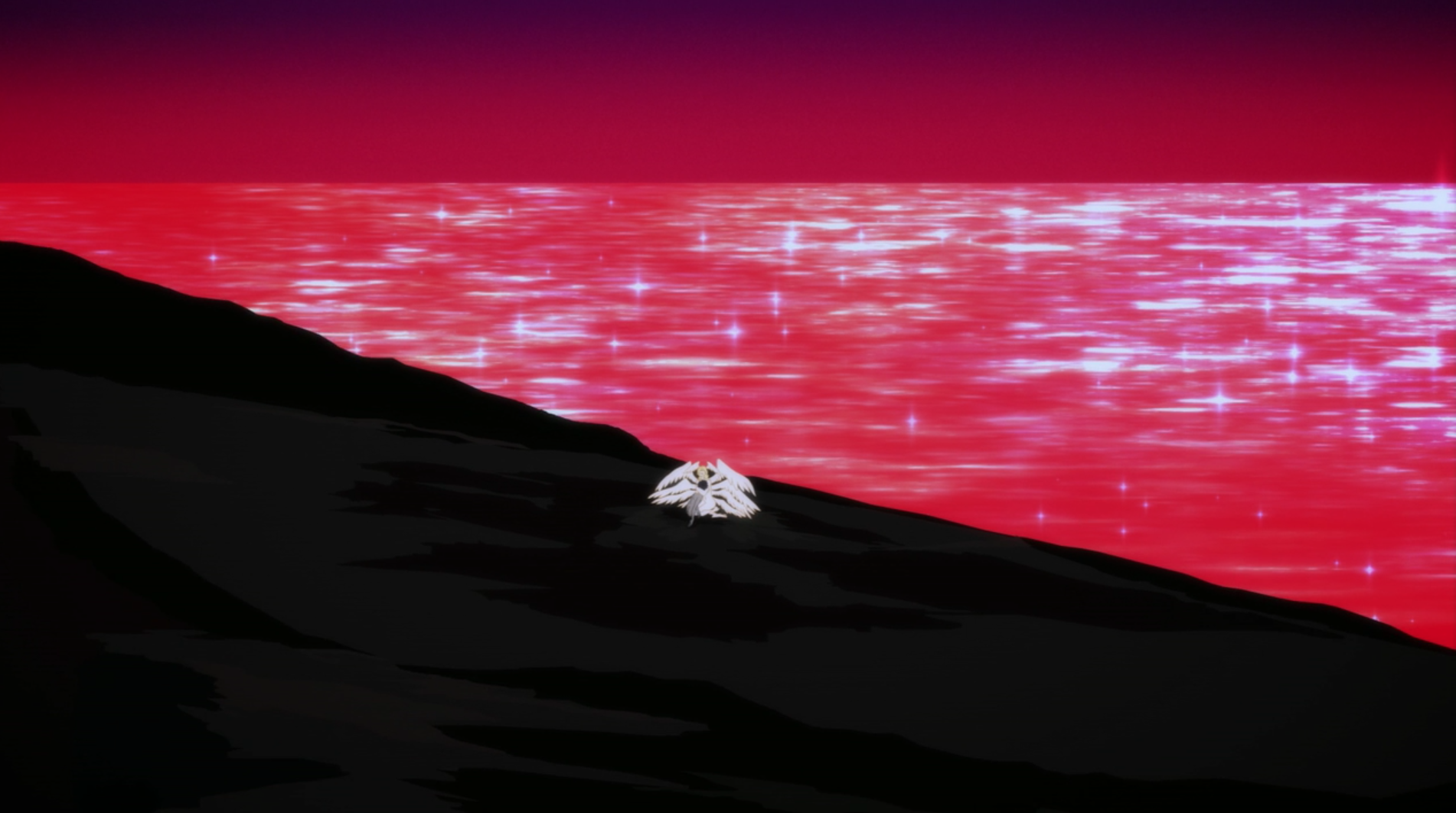

In the final episode, it’s revealed that Ryo is actually Satan, which explains . . . a lot, such as his nihilistic tendencies and lack of compassion. As Satan, they are presented as an intersex being, a casualty of a battle with God who was cast down to Earth. They side with the demons over the humans and find themself caught in an endless war during which the demons and humans completely eliminate each other, leaving alive only Akira and Satan.

After the two battle (because how could they not after all this??), they’re shown from the waist up talking on a small mound of land within a vast red sea—i.e., all that’s left of Earth—and Satan confesses that they’re in love with Akira. But the gut-punch comes when the camera pans back to reveal Akira’s severed torso and we realize he was killed by Satan during their battle. Satan, only coming to terms with their humanity and capability to love in the wake of utter devastation, must repeat this same cycle for all of eternity as they cry, holding what remains of their loved one in their hands.

Image: Netflix

It’s brutal, the kind of ending that makes you want to immediately call your parents, visit old friends, and hug everyone you’ve ever loved. But it posits a fair question: Is love worth the inevitable sorrow in its wake? The obvious answer, unless you have sociopathic tendencies or are secretly Satan yourself, is yes, of course. Humans need love in order to be, well, human. But on the other hand, if Satan had never fallen in love with Akira, the elimination of the entire human race would simply be a fun pastime rather than a heart-wrenching moment of humanity. As Satan, loving Akira is their only flaw, whereas the humans’ flaw is not loving each other more.

They have become the very demons they were afraid of.

Once Ryo reveals the existence of demons, people—as well as entire countries—are quick to turn on one another. (There’s even a Tr*mp cameo to really drive this point home.) Akira and his friend Miki Makimura, whose family he lives with, seemingly become the last vestiges of hope for humanity, embodying pure compassion, love, and empathy. But when Miki is violently stabbed in the back by another human and Akira sees her lifeless head bobbing up and down on a stick, it symbolizes the end of people being people. They have become the very demons they were afraid of. This particular episode’s title, which is also what Akira screams in a fit of rage and sadness, is a fitting thesis for the whole series: “Go to Hell, You Mortals!”

Image: Netflix

In broad strokes, the show is a damning portrait of the worst we can be: violent, selfish, and unkind. But, before everything goes to hell, some of the most memorable moments arise out of genuine love and decency. Miki’s father, for example, breaks down as he watches his son, Taro, turn into a demon and consume his wife—but he’s unable to shoot him. In another scene, Devilman jumps in front of humans being tortured by other humans and gets rocks thrown at him, but a young boy walks up and hugs his leg, which leads to others putting down their weapons and hugging him. After all that, Miki posts on social media about how pure of heart Akira is, which inspires others to have the courage to reveal themselves as devilmen and fight the demons alongside Akira.

Society is quick to turn on them, but the show urges us to find the humanity in everyone, regardless of our differences.

We should strive to imitate such courageous acts in our lifetime, protecting others when they’re in pain or showing support of marginalized communities with something as simple as a social media post. The devilmen, who are human despite having something thrust upon them that’s out of the norm, represent POC, women, LGBTQ people—any minority group, really. Society is quick to turn on them, but the show urges us to find the humanity in everyone, regardless of our differences.

This message seems especially purposeful given the show’s (admittedly surprising) queer representation. In the background of the demon orgy scenes, we see men with men, women with women. In episode six, we’re introduced to Moyuru Koda, a rival track athlete turned devilman, in a scene showing him having sex with his boyfriend, Junichi, before accidentally turning into a demon and killing him. We later see Koda break down emotionally, once in bed and another time in a parking garage while rewatching a video of Junichi. It’s both sweet and heartbreaking, a combination of images we don’t typically see in media: a man unashamedly crying, a non-heterosexual man showing genuine feelings for another man, a same-sex romance, et cetera. It’s given an appropriate weight, too: Koda’s breakdown lasts a full forty seconds and culminates in him turning into a half-human, half-demon blob, a visual representation of his internal struggle.

Image: Netflix

We also meet Miko Kuroda, a girl who’s spent her whole life running and training for track but eventually gets overshadowed by the faster and more popular Miki, Akira’s friend, who’s also known as “the witch of track and field.” (Miko’s real name is Miki, too, but people started calling her Miko to differentiate the two.) She spends the entire series in Miki’s shadow, envious and angry, but toward the end, Miko confesses her love for Miki:

Miko: You’re so annoying. I seriously hated you.

Miki: Yeah, I knew that.

Miko (falling to her knees): But . . . I loved you.

Miki (sweetly): I knew that too.

The confession isn’t inherently romantic; it’s a combination of adoration, longing, and, yes, maybe some romance, too. But it’s a loaded love that transcends gender, sexuality, and even demons (lol), culminating in Miko sacrificing herself to try to save Miki.

Image: Netflix

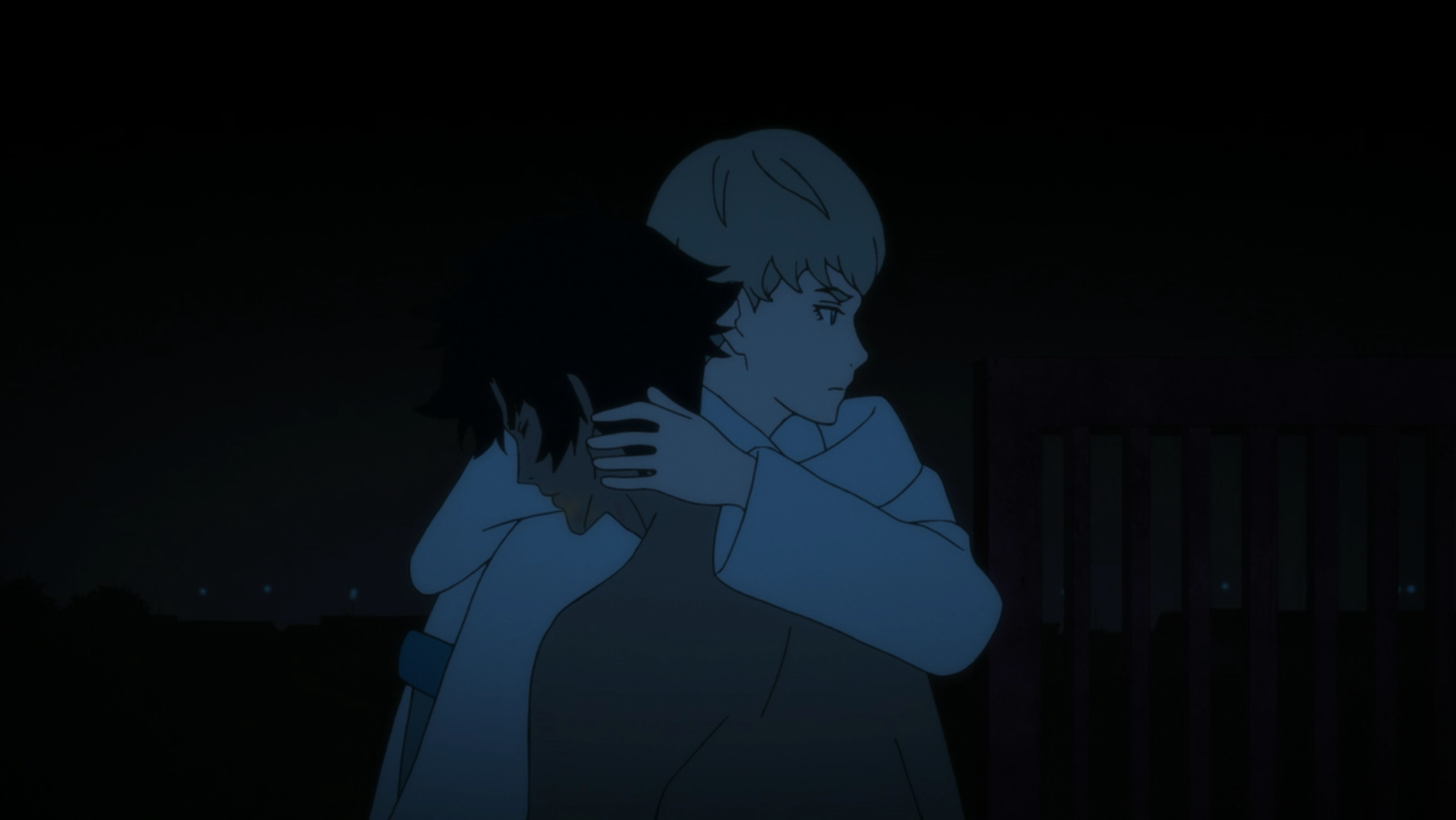

And finally, of course, there’s the intersexual Satan’s love for the Devilman Crybaby, which slowly grew in strength as they lived as the two boys Ryo and Akira. One of the most unnecessary scenes in the entire show is also one of my favorites: While Ryo is working, Akira checks out Ryo’s giant pool. “Don’t you ever swim in it?” Akira asks.

“Nooo thanks,” Ryo says.

“What a waste! You should swim,” Akira says. “The weather’s good, water’s warm—do some laps!” And then he pushes Ryo in. They splash around for a second before it cuts back to Ryo on his computer again and Akira toweling off, as if nothing had happened.

In the scope of the whole series, which includes wild orgy parties, the destruction of our entire planet, and centuries-long cosmological wars, it’s a microscopic moment, but it’s one of the most playful, one of the most relatable, and one of the most human. In spite of its nihilism, Devilman Crybaby reminds us to do one thing above all else—and it doesn’t matter how, why, or with whom: We must love. Our humanity depends on it.